Common Questions on Powers of Attorney: Difference between revisions

Drew Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Drew Jackson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

A power of attorney deals '''only''' with your financial and legal affairs. It does not enable your attorney to make decisions about your personal care and health care. For example, a power of attorney would not allow your attorney to consent to health care on your behalf or to make decisions about where or with whom you will live. | A power of attorney deals '''only''' with your financial and legal affairs. It does not enable your attorney to make decisions about your personal care and health care. For example, a power of attorney would not allow your attorney to consent to health care on your behalf or to make decisions about where or with whom you will live. | ||

Under BC law, if you want to have someone of your choice make decisions about your personal care and health care when you no longer can, you can make | Under BC law, if you want to have someone of your choice make decisions about your personal care and health care when you no longer can, you can make a '''representation agreement'''. In a representation agreement, you name whoever you want - such as a friend, relative, spouse, or adult child - to make personal and health care decisions for you, or assist you in making decisions, if you become incapable of making decisions on your own. | ||

Another option to be aware of is an '''advance directive'''. In an advance directive, you can write instructions to your health care provider about what kind of health care treatment you want and don’t want, including life support or life-prolonging medical interventions. No one will be asked to make a decision for you when the advance directive applies. | Another option to be aware of is an '''advance directive'''. In an advance directive, you can write instructions to your health care provider about what kind of health care treatment you want and don’t want, including life support or life-prolonging medical interventions. No one will be asked to make a decision for you when the advance directive applies. | ||

Revision as of 22:43, 24 April 2017

| This information applies to British Columbia, Canada. Last reviewed for legal accuracy by Kevin Smith in March 2017. |

What is a power of attorney?

A power of attorney is a legal document. When you make a power of attorney, you give someone the legal power to take care of financial and legal matters for you. This might include paying bills, depositing or withdrawing money from your bank account, investing your money, or selling your home.

The person you give this power to is called the attorney. In this case, attorney does not mean lawyer.

You are called the adult.

A power of attorney does not give the attorney authority to make decisions about your health care or personal care. It covers financial and legal matters only.

A power of attorney is different from a will, which provides for the distribution of the things you own after your death. A power of attorney is a way to plan for the handling of your affairs during your lifetime.

Why have a power of attorney?

A power of attorney is a simple and inexpensive way to plan ahead and choose who will help you with your financial and legal affairs.

There are several reasons you might make a power of attorney.

A power of attorney can be a good option if you are physically unable to look after your affairs due to travel or injury.

|

"I want to spend the summer visiting my grandchildren in France. I'll be gone for several months, and I'd like to enable my niece to pay my bills while I'm away. I learned I can do that by making a limited power of attorney. In it, I authorized my niece to access my bank account only to deposit my pension cheques and pay my bills, and only until I come home from my trip." - Helga, Victoria |

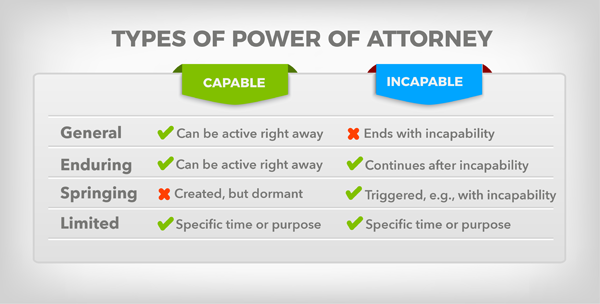

A power of attorney set up so that someone can look after your affairs while you are traveling would be an example of a limited power of attorney. This is also called a specific power of attorney. Your attorney’s powers are limited to a specific task or a specific period of time. For example, you might give someone power of attorney to sign the papers on the sale of your home while you’re out of the country on vacation.

|

"My husband William had an accident at work. He is in hospital in a coma. We have a joint bank account, so I can pay the bills. But our car is in William’s name and the insurance is due. William can’t sign. I wish William had made an enduring power of attorney appointing me as attorney. That way I could renew the insurance." - Anita, Burnaby |

Another reason you might make a power of attorney is to prepare for the possibility you become mentally incapable due to age, accident or illness. With an enduring power of attorney, you can appoint someone to act on your behalf for financial and legal affairs, and specify that the appointment continues in effect - or endures - if you become incapable of making decisions. (With a general power of attorney, the appointment ends when you become mentally incapable.)

For more on enduring powers of attorney, see the section "Enduring Power of Attorney".

A power of attorney can also be set up to come into effect only when something happens to trigger it. This is called a springing power of attorney. You can appoint someone to act on your behalf if the triggering event happens. The triggering event can be when you become mentally incapable. For example, the appointment can be worded to come into effect “when two physicians have determined that I am no longer capable of managing my affairs”. Such a springing power of attorney is not active until you are incapable.

The types of power of attorney are not mutually exclusive. For example, an enduring power of attorney or a springing power of attorney can be limited to a specific purpose or time period.

Are there other options to plan for the future?

Yes. In BC, an enduring power of attorney is the most common document used to give another person the authority to take care of your financial and legal affairs in the event you become mentally incapable.

But there are other options.

- In a representation agreement, you can name someone of your choice to make decisions for you when you can no longer manage on your own. The person you name as your “representative” can make personal care and health care decisions for you. With a “section 7 representation agreement”, the representative can also be authorized to handle “routine management” of financial affairs and most legal matters. For example, your representative can pay your bills, deposit your pension and other income, purchase food and other personal care services, and make investments for you. However, they can not handle financial matters beyond the routine, such as buy or sell your real estate property or take out a new loan in your name.

- In a trust agreement, you can put all your property and income in a trust. You can name someone of your choice to be the trustee, and spell out terms of how the property is to be managed. The trust continues if you become incapable, and can even survive death, ensuring your affairs continue to be managed in a way that is consistent with the terms in the trust.

- If your finances are not complicated, a pension trusteeship can be set up. Let’s say your only source of income is federal income security programs such as Old Age Security and the Canada Pension Plan, and your expenses are just rent, food and utilities. In that case, a capable family member or friend can sign up with the income security programs to receive your pension funds as trustee to pay the rent and bills.

- If your income is directly deposited into your bank account, you could set up a joint bank account with a trusted relation or friend. That person could help you with paying bills and making withdrawals. You need to be aware of the risks of a joint bank account. For example, any person named on the joint account is able to withdraw money from the account at any time. As well, note that in many cases, joint bank accounts include the “right of survivorship”. This means that if one of the account holders dies, the surviving account holder becomes the owner of the account.

If you become incapable of making decisions independently and you do not have an enduring power of attorney or one of these other planning tools in place, your family may have to go to court to get the legal right to manage your affairs.

What about health care decisions?

A power of attorney deals only with your financial and legal affairs. It does not enable your attorney to make decisions about your personal care and health care. For example, a power of attorney would not allow your attorney to consent to health care on your behalf or to make decisions about where or with whom you will live.

Under BC law, if you want to have someone of your choice make decisions about your personal care and health care when you no longer can, you can make a representation agreement. In a representation agreement, you name whoever you want - such as a friend, relative, spouse, or adult child - to make personal and health care decisions for you, or assist you in making decisions, if you become incapable of making decisions on your own.

Another option to be aware of is an advance directive. In an advance directive, you can write instructions to your health care provider about what kind of health care treatment you want and don’t want, including life support or life-prolonging medical interventions. No one will be asked to make a decision for you when the advance directive applies.

Legal capacity requirements

In considering the various planning options, a key factor to be aware of is that there are different legal capacity requirements. Legal capacity refers to a person’s ability to make binding decisions or agreements.

Someone who doesn’t have sufficient legal capacity to make an enduring power of attorney may still be able to make a representation agreement. A person can make a section 7 representation agreement even if they cannot manage their routine financial affairs or look after their daily needs. This makes a section 7 representation agreement a very useful “last resort’’ document when someone has not made any other planning documents and they are starting to lose their capacity.

A lawyer or notary public can guide you on which planning documents best fit your situation.

You can still make decisions

Having a power of attorney does not remove your decision-making rights. Decision making is not given away; it is shared between you and the attorney whenever possible. Your attorney cannot override a decision made by you while you are capable. Your attorney has a legal duty, to the extent reasonable, to foster your independence and encourage your involvement in any decision-making that affects you.

Choosing your attorney

When making a power of attorney, you can choose as your attorney someone who is:

- age 19 or older, and

- able to understand the responsibilities involved.

The law has two restrictions on who can be appointed as an attorney. You cannot appoint:

- A caregiver who is paid to provide you with personal or health care services.

- An employee at a facility where you live if the facility provides health or personal care services.

These restrictions do not apply if the person providing the care is your child, parent or spouse.

Most people choose their spouse, a family member or a friend as their attorney.

For a fee you can choose a trust company as your attorney. You can also name the Public Guardian and Trustee (a government official), but you need to check in with them first.

|

Your attorney will have significant power, so choose somebody you trust, and who is comfortable with financial matters. Take the time to talk with that person about what you want and would expect them to do. |

You can appoint more than one person as your attorney. If you do, you must write in the document whether they will act together or individually. If you don't specify, the default is that they must act together.

What if something happens to your attorney?

If you name only one attorney, it is very important to name an alternate who will take over if something happens to your attorney. However, you also need to describe very clearly the circumstances when an alternate may take over.

Can your attorney be someone who lives in another province?

Yes. The person you name as your attorney does not have to live in British Columbia.

Do you have to pay your attorney?

Your attorney is entitled to be paid back for any reasonable out-of-pocket expenses. If you want to pay your attorney a fee, you must write this in the power of attorney. The document must authorize the fee and set out the rate.

If a trust company or the Public Guardian and Trustee is your attorney, they will ask you to sign an agreement that says they can charge fees.

The attorney's powers and responsibilities

The attorney is like your agent. He or she must act honestly, in good faith and in your best interests. Your attorney must keep careful records of any financial activities, and must keep your affairs separate from his or her own.

A general power of attorney gives your attorney the power to do anything financial or legal that you can’t do for yourself. This could include dealing with bank accounts, getting information from Canada Revenue Agency in order to do your income tax, insuring or selling your car, or selling real estate.

What can you do to prevent misuse of your power of attorney?

Before you make a power of attorney you may want to talk to a friend, family member, community advocate, or legal professional. You can also insist that your attorney get legal advice about his or her responsibilities.

Attorneys must keep accurate records, and attorneys must not take a personal benefit from the person’s assets. Be sure you choose someone you trust. If possible, name more than one person. Talk to these people before you appoint them and make sure they understand what you expect from them, and when you expect them to act.

Even a power of attorney that takes effect as soon as it is signed does not have to be used until you need help. You may want to give the power of attorney document to someone else you trust, and tell him or her when to give it to the attorney.

You can put limits on the power you give your attorney. You can require the attorney to keep records of your finances and show you those records regularly. You should also review your bank statements.

Are there special requirements relating to real estate?

If you want your attorney to have the power to sell your real estate property or deal with mortgages or easements, there are special requirements.

You must go to a lawyer or notary public to have the document prepared, and here are a few things you should know:

- Your power of attorney must use the exact name that is listed on your real estate property at the Land Title Office. For instance, if the name on the property deed is “Chung Hon Lee”, you cannot use “C.H. Lee” in the power of attorney. If you are not sure of the exact name, do a search at the Land Title Office.

- A power of attorney for real estate gives your attorney the power to sell or transfer property to someone else, but not to him or herself. If you want to include that power, it has to be specifically written in. Discuss this with your lawyer or notary.

- You must sign the power of attorney in the presence of a lawyer or notary, and the lawyer or notary must also sign.

- You must register the power of attorney at the Land Title Office and pay the registration fee. Check at your local Land Title Office for the current fee. You can wait to register it, but don’t wait to check with the office to make sure it meets the requirements.

- A power of attorney for real estate ends automatically in three years unless it is an enduring power of attorney or you say in the power of attorney “Section 56 of the Land Title Act does not apply”.

Timing of a power of attorney

When does the power of attorney start?

A power of attorney can be written to come into effect as soon as it is signed. However, even a power of attorney that comes into effect on signing it does not have to be used immediately. Make sure your attorney knows when you want him or her to act.

When does the power of attorney end?

A limited power of attorney ends when the job it describes is done, or on the date it specifies. For example, if you make a limited power of attorney to sell a piece of property, the power of attorney ends when the property is sold. A general power of attorney automatically ends in these circumstances:

- If you become incapable, unless you have an enduring power of attorney clause that makes a power of attorney continue to have effect if you are incapable.

- If your attorney dies, unless you name an alternate or more than one attorney.

- If you die.

- If the court appoints a committee to make decisions for you. A committee (pronounced caw-mi-tay or caw-mi-tee, with emphasis on the end of the word) is a person or body (such as the Public Guardian and Trustee) appointed by the court to look after your legal and financial affairs in the event that you become incapable of managing your affairs.

You can also cancel a power of attorney at any time.

If you made a power of attorney ten years ago, is it still good?

Yes. However, you should check it over to make sure that it will do what you want and the information is accurate. You may decide to make a new one.

It’s a good idea to review all your financial affairs (including your will) every two or three years. Addresses change, and so do people’s lives. Stay up to date.

Questions about jurisdiction

What about powers of attorney made in another province or country?

Each province in Canada has its own laws and procedures for powers of attorney. This publication applies to residents of British Columbia who have finances and property in BC. For information about powers of attorney in another province or country, it’s best to consult a legal professional. You may also want to check your local library or bookstores for a book called Power of Attorney Kit by Self Counsel Press, or contact a public legal education and information provider in your province.

If you have property in another province or territory, will your BC power of attorney apply?

Possibly. However, the safest approach is to check with a lawyer in that province or territory.

Is a power of attorney made in one province okay in another?

It is likely the power of attorney made in one province will be recognized in another. However, it may not be effective in dealing with all real estate matters.

Preparing the power of attorney

|

The BC Ministry of Justice has an enduring power of attorney form available online. You do not have to use this form, but it gives you an idea of how to make a power of attorney. |

Most people will go to a notary public or a lawyer to prepare their power of attorney. In fact, you must sign the power of attorney in the presence of a notary public or lawyer in order for the power of attorney to be recognized at the Land Title Office (see above).

In order for your attorney to have the power to sell your vehicle or renew its insurance, your power of attorney may need to be notarized. Notarizing means a notary public puts his or her seal on the document when you make it, to confirm that you and the witness signed it in front of him or her.

Particularly if you have a complicated or unusual situation, it’s best to get some professional help. If you go to a lawyer or notary public, find out how much they will charge you. Phone around and compare prices. See the "Where to Get Help" section for help finding a legal professional.

| ||||||||||||||||||||