Indian Act (Legal Information for Indigenous People: National Edition)

Status

"Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the question of whether a certain person 'belonged' to a First Nation was determined by the cultural rules and practices of that particular nation. In the 1850s, however, the governments of the Canadian colonies began to use laws to establish which individuals, in the government’s view, validly belonged to a particular group of First Nations people. These rules, which eventually became part of the first Indian Acts, had little or nothing to do with the cultural practices and family structures of First Nations peoples."

- Assembly of First Nations: Guide to Membership Codes, Legal Affairs and Justice, p5, March 31, 2020

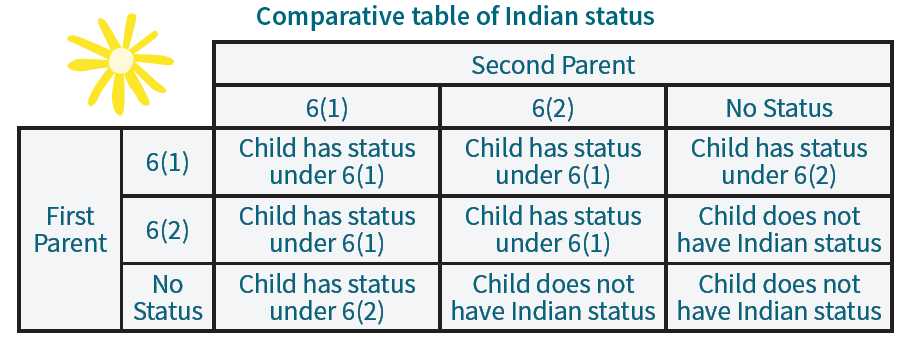

The Indian Act has enabled the Canadian government to define who qualifies as an "Indian" in the form of "Indian" Status. Under the Indian Act, Status is the legal standing of a person who is registered under the Indian Act. To make it more complicated, an Indigenous person could be eligible to be registered under either Section 6(1) or 6(2) of the Indian Act.

A person may be registered under section 6(1) if both of their parents are, or were, registered or entitled to be registered, regardless if their parents were registered under 6(1) or 6(2). If a person who is registered under section 6(1) has a child with someone without status, their children will be able to register under 6(2).

Indigenous people with "Status" may be eligible for programs and services such as education funding, non-insured health benefits programs, Treaty payments and potential tax benefits. While these 6(1) or 6(2) designations have no effect on the services, benefits, or rights that an individual possesses, they could affect their ability to pass on Status to their children.

For example, if a person is registered under section 6(2) has a child with someone without status, their children will not be able to register for Status. This is known as the "second generation cut-off" and means that a person loses their right to pass on Status after two consecutive generations of parenting with a person who is not entitled to Status.

Bill S-3 Changes to Indian Act

The law about eligibility for Indian status changed significantly between 1985 and 2019 in response to Indian Act amendments that remedied gender discrimination against women, many of whom lost their Indian status for marrying non-Indian men. The discrimination impacted thousands of women and their descendants.

The most recent of the changes to the Indian Act are under Bill S-3 and have expanded further who may be eligible for Status. These changes could mean that you or someone you know may now be entitled to registration.

Generations of persons, including those who may have been previously denied entitlement, are now able to register. The changes in registration rules for these individuals mean that their children might also become allowed to register.

Bill S-3 ensures the entitlement of all descendants of women who lost status or whose names were removed from band lists for marrying a non-entitled man going back to 1869.

To know if you are entitled to registration, ask yourself:

- Did my mother, grandmother, or great-grandmother lose status due to:

* marriage to a non-entitled man before April 17, 1985? * being born outside of marriage between an entitled father and non-entitled mother between September 4, 1951, and April 16, 1985?

- Did one of my parents, grandparents or great-grandparents:

* lose status because of their mother's marriage to a non-entitled man before April 17, 1985? * have their name removed from the Indian Register or from a band list because their father was not entitled to status?

Further, under Bill S-3, individuals registered under section 6(2) could be entitled to register under section 6(1)(c) and be able to pass on Status if they meet all of the following conditions:

- They are a direct descendant of a woman who lost her status or was removed from band lists because of marriage to a non-Indian man.

- They were born prior to April 17, 1985, and are a direct descendant of a man who lost his status or was removed from band lists because of marriage to a woman who was not eligible for Indian status.

- They are a direct descendant of a person who was enfranchised, or their spouse or common-law partner.

In addition, anyone previously entitled under the 6(1)(c) paragraphs of the Indian Act are now being entitled under the new 6(1)(a) paragraphs.

Lastly, if you, your mom or your grandmother were unmarried and voluntarily enfranchised as a result between September 4, 1951, and April 16, 1985, you may be eligible for a Category amendment (ISC will automatically do this but if you applied and were denied then you will need to reapply).

Bill S-3 Additional Changes

If your parent is not listed on your birth certificate: Bill S-3 added a new provision to the Indian Act that allowed for greater flexibility in the case of unknown or unstated parentage. The applicant can present various forms of evidence and the Indian Registrar is to make a determination on whether it is more likely than not that the applicant has a parent, grandparent, or ancestor entitled to Status. This decision will affect your eligibility for Status.

Adoption: A child can be registered under the Indian Act through their birth parents or through their adoptive parents as long as they were adopted as a minor. For an adopted person to be registered, at least one parent, either adoptive or birth, must be registered or entitled to be registered under section 6(1) of the Indian Act.

Legal or Custom Adoption: A legal adoption is a court process that includes legal documents and an adoption order. A custom adoption follows Indigenous cultural traditions. If you were adopted as a minor (17 years of age, or less in Alberta) by "Indian" parents through legal or custom adoption you can register for Indian Status.

For identity issues, you may:

- use your traditional name on your Status card.

- select a non-binary gender marker on your application or status card. Your gender marker does not need to match the gender listed on other documents you submit with your application.

| Assembly of First Nations Fact sheets about Band Membership vs. Indian Status: https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/20-03-31-Draft-Membership-Guide-final.pdf# |

| © Copyright 2024, Bella Coola Legal Advocacy Program (BCLAP). |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||