Indian Act (Legal Information for Indigenous People: National Edition)

Status

"Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the question of whether a certain person 'belonged' to a First Nation was determined by the cultural rules and practices of that particular nation. In the 1850s, however, the governments of the Canadian colonies began to use laws to establish which individuals, in the government’s view, validly belonged to a particular group of First Nations people. These rules, which eventually became part of the first Indian Acts, had little or nothing to do with the cultural practices and family structures of First Nations peoples."

- Assembly of First Nations: Guide to Membership Codes, Legal Affairs and Justice, p5, March 31, 2020

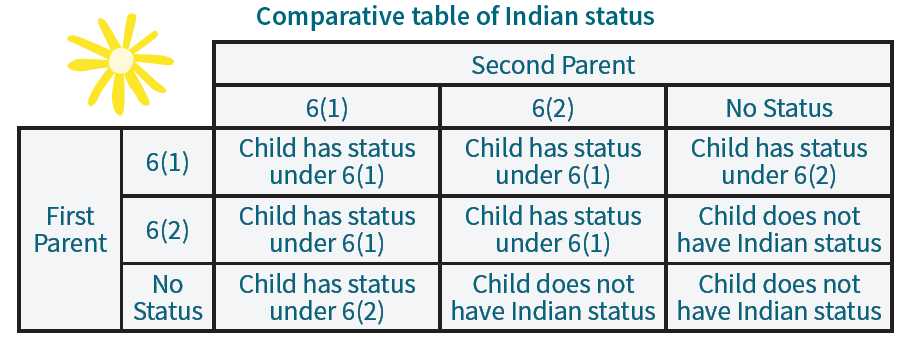

The Indian Act has enabled the Canadian government to define who qualifies as an "Indian" in the form of "Indian" Status. Under the Indian Act, Status is the legal standing of a person who is registered under the Indian Act. To make it more complicated, an Indigenous person could be eligible to be registered under either Section 6(1) or 6(2) of the Indian Act.

A person may be registered under section 6(1) if both of their parents are, or were, registered or entitled to be registered, regardless if their parents were registered under 6(1) or 6(2). If a person who is registered under section 6(1) has a child with someone without status, their children will be able to register under 6(2).

Indigenous people with "Status" may be eligible for programs and services such as education funding, non-insured health benefits programs, Treaty payments and potential tax benefits. While these 6(1) or 6(2) designations have no effect on the services, benefits, or rights that an individual possesses, they could affect their ability to pass on Status to their children.

For example, if a person is registered under section 6(2) has a child with someone without status, their children will not be able to register for Status. This is known as the "second generation cut-off" and means that a person loses their right to pass on Status after two consecutive generations of parenting with a person who is not entitled to Status.

Bill S-3 Changes to Indian Act

The law about eligibility for Indian status changed significantly between 1985 and 2019 in response to Indian Act amendments that remedied gender discrimination against women, many of whom lost their Indian status for marrying non-Indian men. The discrimination impacted thousands of women and their descendants.

The most recent of the changes to the Indian Act are under Bill S-3 and have expanded further who may be eligible for Status. These changes could mean that you or someone you know may now be entitled to registration.

Generations of persons, including those who may have been previously denied entitlement, are now able to register. The changes in registration rules for these individuals mean that their children might also become allowed to register.

Bill S-3 ensures the entitlement of all descendants of women who lost status or whose names were removed from band lists for marrying a non-entitled man going back to 1869.

To know if you are entitled to registration, ask yourself:

- Did my mother, grandmother, or great-grandmother lose status due to:

- marriage to a non-entitled man before April 17, 1985?

- being born outside of marriage between an entitled father and non-entitled mother between September 4, 1951, and April 16, 1985?

- Did one of my parents, grandparents or great-grandparents:

- lose status because of their mother's marriage to a non-entitled man before April 17, 1985?

- have their name removed from the Indian Register or from a band list because their father was not entitled to status?

Further, under Bill S-3, individuals registered under section 6(2) could be entitled to register under section 6(1)(c) and be able to pass on Status if they meet all of the following conditions:

- They are a direct descendant of a woman who lost her status or was removed from band lists because of marriage to a non-Indian man.

- They were born prior to April 17, 1985, and are a direct descendant of a man who lost his status or was removed from band lists because of marriage to a woman who was not eligible for Indian status.

- They are a direct descendant of a person who was enfranchised, or their spouse or common-law partner.

In addition, anyone previously entitled under the 6(1)(c) paragraphs of the Indian Act are now being entitled under the new 6(1)(a) paragraphs.

Lastly, if you, your mom or your grandmother were unmarried and voluntarily enfranchised as a result between September 4, 1951, and April 16, 1985, you may be eligible for a Category amendment (ISC will automatically do this but if you applied and were denied then you will need to reapply).

Bill S-3 Additional Changes

If your parent is not listed on your birth certificate: Bill S-3 added a new provision to the Indian Act that allowed for greater flexibility in the case of unknown or unstated parentage. The applicant can present various forms of evidence and the Indian Registrar is to make a determination on whether it is more likely than not that the applicant has a parent, grandparent, or ancestor entitled to Status. This decision will affect your eligibility for Status.

Adoption: A child can be registered under the Indian Act through their birth parents or through their adoptive parents as long as they were adopted as a minor. For an adopted person to be registered, at least one parent, either adoptive or birth, must be registered or entitled to be registered under section 6(1) of the Indian Act.

Legal or Custom Adoption: A legal adoption is a court process that includes legal documents and an adoption order. A custom adoption follows Indigenous cultural traditions. If you were adopted as a minor (17 years of age, or less in Alberta) by "Indian" parents through legal or custom adoption you can register for Indian Status.

For identity issues, you may:

- use your traditional name on your Status card.

- select a non-binary gender marker on your application or status card. Your gender marker does not need to match the gender listed on other documents you submit with your application.

| Assembly of First Nations Fact sheets about Band Membership vs. Indian Status: https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/20-03-31-Draft-Membership-Guide-final.pdf# |

Applying for Status

Step 1: Get the Application Forms

Online, in person (ISC Regional Office), request by mail or at Band Office.

Step 2: Do you need a Guarantor?

- Are you applying by mail?

- Are you using a photo ID that doesn't meet all the requirements?

- Are you submitting an application on behalf an applicant?

Your guarantor must:

- Not be your parent or guardian

- Be 18 years or older

- Reside in Canada or the U.S.

- Have known you personally for at least 2 years

- Be reachable to verify information

- Have a Secure Certificate of Indian Status (SCIS) that they applied for when they were 16+

- OR

- Is one of the listed qualified professions

Step 3: Gather Proof of Identity

If you are applying for a Secure Certificate of Indian Status (SCIS), you must include 2 copies of a Canadian passport-style photo in your application. Note: You are not required to apply for an SCIS if you are only applying for Status.

If anyone listed on the application has a different name from the one on their required documents, you must provide either:

- An original document linking the previous name to the current name, e.g. marriage certificate.

- OR

- a photocopy of the above document with valid ID that has the current name as it appears on the application

Include the Guarantor Declaration in your application.

For Adult in-person applications:

- Original birth certificate with the parents' names.

- Original acceptable valid ID.

For Adult applications by mail:

- Original birth certificate with the parents' names.

- Photocopies of ID, signed by a guarantor.

- A Guarantor Declaration.

For Child/Dependent in-person applications:

- Original birth certificate with the applicant's parents' names.

- Original acceptable valid ID of the parent/legal guardian.

For Child/Dependent applications by mail:

- Original birth certificate with the applicant's parents' names.

- Photocopies of ID for each of the applicant's guardians, both signed by a guarantor.

- A Guarantor Declaration.

Step 4: Gather Proof of Ancestry

You will need to gather primary and secondary evidence about your parents or grandparents.

- Primary evidence includes:

- Birth, marriage, or death certificates.

- Secondary evidence includes:

- Church records, newspapers, or sworn statements about your ancestry relevant to entitlement for Status.

Try to gather as much information as you can about your parents and grandparents. Requested information includes:

- Legal names.

- Dates of birth.

- Band names or First Nations.

- Registration numbers.

- Contact information.

- Adoption information (if applicable).

- Even if you don't have all the information, you can still apply.

Step 5: Sign and Date your Application

Note: A parent/guardian will need to sign the application for a dependent.

Step 6: Submit your Application

You can submit your application either in person or by mail.

If the Registrar denies your Indian Status, you can protest the decision. If you feel you are entitled under a different category of the Indian Act, or if your name is taken off the Indian Register, or you disagree with your addition to, omission, or deletion from a particular band, you may be able to file a protest against the Registrar's decision. You must submit your protest within three years from the date of the Registrar's decision.

If you are worried about missing this deadline, submit your application as soon as possible and follow up with the documents or proof you need. Keep in mind: it can take at least six months to receive a decision on your application.

Note: A Status application can be expedited for elders or in cases of serious illness.

| Indigenous Services Canada’s Website on how to apply for Status: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032472/1572459733507 |

You can submit your application in person at any ISC Regional Office or First Nation or Band Office (if applicable).

To submit your application by mail, use the following addresses:

- General Applicants:

- National Processing Unit

- Indigenous Services Canada

- 10 Rue Wellington

- Gatineau QC, K1A 0H4

- Bill S-3 Applicants (those applying based on previously denied or revoked Status due to discrimination):

- Application Processing Unit

- Indigenous Services Canada

- Box 6700

- Winnipeg MB, R3C 5R5

Wills

To be valid, a will under the Indian Act must:

- Be in writing (audio/video wills or oral instructions are not accepted).

- Be signed by the will-maker.

- Give away something the will-maker owns.

- Be intended to take effect upon death.

- Have two adult witnesses (not beneficiaries or their spouses).

- Be dated.

The person writing the will must be:

- A "Status Indian" under the Indian Act.

- Considered "ordinarily resident on-reserve."

- 16 years or older.

- Free from pressure or influence.

In addition to these requirements, it is important to include the following in your will:

- Name an executor and an alternate to manage your estate.

- Name who you want to care for your children.

- Provide funeral directions.

- Make gifts of specific assets (e.g., house, boat, car, jewelry, art, etc.).

- State the residue/remainder of the estate (what is left over after debts and gifts have been paid).

For step-by-step directions, use the template in "Writing Your Own Will – A Guide for First Nations People Living on Reserve (Revised 2019)." Writing Your Own Will Guide

Indigenous people on Reserve can leave their home in a will to people who are members of their Band or entitled to be, as long as the house is located on a Certificate of Possession lot (CP). Although a CMHC "rent to own" house cannot be given away in a will, including this in your will still helps inform your family and the Band of your wishes.

First Nations people not living on a Reserve at the time of death are subject to the wills legislation of the jurisdiction where they lived.

Estates

An estate is all of the money and property (and debts) left after someone dies. Estates fall under federal jurisdiction with Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) when someone who is "ordinarily resident" on reserve passes away (meaning if they were living away from the reserve, it was only for school, medical reasons, etc.).

The person named in the will as the executor has the job of settling the affairs of the deceased: paying bills, filing taxes, closing accounts, and generally following the wishes of the deceased as stated in the will.

If there is no will, then the family (and ISC) will appoint an administrator. ISC will send the administrator a certificate showing their appointment.

Executors and family members are not liable for the debts of the deceased. The executor's role will be to pay bills from the money in the estate before any beneficiaries are paid. If there is no money, then no bills get paid.

If your common-law partner or spouse has passed and you are wondering how your home on reserve is affected, the Family Homes on Reserve and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act will likely apply. If so, you:

- Are entitled to remain in the home for 180 days, even if renting and even if not a Band member.

- Can apply under the Act for exclusive occupation of the home beyond the 180 days (depends on situation).

- May apply within 10 months of the death for a court order to determine entitlement.

Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) is responsible for estate services for First Nations in all provinces. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) is responsible for estate services for First Nations in the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

Supporting First Nations estate claims in class action settlements: If you think your family member or friend's estate is impacted by a settlement, please contact ISC to discuss options that may be available for the estate at Estate Services.

For a step-by-step description of what needs to be done, see Estate Administration On Reserve. Estate Administration On Reserve Guide For questions, contact Indigenous Services Canada. ISC Website

If a First Nations person was not living on a Reserve at the time of death, the estate falls under the jurisdiction of the province, territory, or country where they lived.