Understanding the Legal System for Family Law Matters

In its broadest sense, the legal system refers to how laws and policies are made, how we decide which problems are legal problems, all of the ways that legal problems are addressed, all of the people involved in resolving legal problems — including politicians, government staff, judges, prosecutors, lawyers, court administrators, mediators, arbitrators, and mental health professionals — and all of the people experiencing legal problems. This chapter takes a narrow view of the legal system, but it's the view that we see in movies and on television, where all legal problems are resolved in court by a judge after listening to lawyers arguing about the law.

The chapter begins with a brief overview of the basic elements of our legal system and how they work together. The sections that follow discuss the legal system in more detail, covering the court system, the law, and the lawyer-client relationship, in the context of family law disputes. It finishes by talking about the barriers and obstacles people often experience in resolving their legal problems, in the Access to Family Justice section.

Introduction

When some families separate, the adults just separate and it's over and done with. For other families, separation raises a bunch of practical and legal problems. If a family includes children, the parents have to decide where the children will mostly live, how they will make parenting decisions, how much time the children will spend with each parent, and how much child support should be paid. If one spouse is financially dependent on the other, they may have to decide whether spousal support should be paid. If the family has property and debt, they'll have to decide who should keep what.

When a family has problems like these, they also have to decide how they'll resolve them. In other words, they need to pick the process they'll use to figure everything out and get to a resolution. Some couples just talk it out. Others go to a trusted friend, family member, elder, or community leader for help. Others use a mediator to help them find a solution. Others go to court or hire an arbitrator.

In that narrow view, the legal system refers to the litigation process. It includes the people who have legal problems, the lawyers who represent them in court, the judge who makes a decision about those legal problems, and of course the laws and rules that guide the court process. It's important to remember, despite what you see on television, that there are other, often better, ways of resolving family law problems than litigation. You can read about negotiation, mediation, collaborative negotiation, and arbitration in the chapter Resolving Family Law Problems out of Court. This chapter, however, mostly talks about the litigation process.

Choosing the right process

Many people see litigation — going to court — as their first and only choice. That might be true if your business partner has broken a deal, if you've had a car accident and ICBC won't pay, or if you're suing some huge corporation. It is certainly not true for family law problems.

Deciding not to litigate

Instead of going to court, you could, for example, sit down over a cup of coffee and talk about the problem. You could hire a family law mediator to help you talk to each other, help identify opportunities for compromise, and help come up with a solution that you're both as happy with as possible. You could hire a lawyer to talk to the other side on your behalf and negotiate a solution for you. There's also collaborative negotiation, a cooperative process in which you and your ex each have your own lawyer and your own coach, and you agree to work through your problems without ever going to court. Then there's arbitration, in which you hire a family law arbitrator who serves as your own personal judge and manages the dispute resolution process that you have designed.

In almost all cases, negotiation and mediation, and even arbitration, are better choices than litigation. They cost a lot less than litigation, they offer you the best chance of getting to a solution that you're both happy with, and they give you the best chance of maintaining a decent relationship with your ex after the dust has settled. A national study of family law lawyers done by the Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family in 2017 showed that lawyers see mediation, collaborative negotiation and arbitration as cheaper than litigation, faster than litigation, and more likely to produce results that are in the interests of their clients and in the interests of their clients' children.

Despite the obvious benefits of avoiding litigation, a lot of people still go to court when they have a family law problem. Why? Usually because they're angry, sometimes because they want revenge. Sometimes they go to court because they see a bigger threat to their personal and financial well-being than really exists; sometimes it's because they can't trust their ex anymore and simply don't know what to do next. Sometimes it's because going to court costs less than hiring a lawyer, a mediator, or an arbitrator. Sometimes it's because the only way we see legal problems being resolved on television is through litigation.

The legal system isn't just about judges and courts, lawyers, and litigation. It also includes negotiation, collaborative negotiation, mediation, and arbitration. If you have a family law problem, litigation isn't your only choice. You have options. (Whatever you decide to do, however, it's very important that you get legal advice from a lawyer in your area since most laws change from province to province. It is important to know about the law, your options, and the range of likely outcomes if you took your legal problem to court.)

Knowing when you need to litigate

Despite its many downsides, there are some situations in which litigation may be your best choice.

Your ex won't talk to you

The thing about negotiation, collaborative negotiation, mediation, and arbitration is that they are all voluntary. You and your ex have to agree to negotiate, mediate or arbitrate. Litigation is not voluntary. When someone starts a court process, the people on the other side have to participate in that process or they risk the court making a decision without hearing from them, called a default judgment.

If you can't get your ex to sit down and talk to you, or if your ex will talk to you but won't commit to a settlement, litigation may be your only choice.

You can't get a deal done

You may need to start a court proceeding if you've tried to resolve things in other ways but can't reach a final settlement no matter how hard you try. For some people, prolonging disagreement and conflict is a way of continuing a relationship beyond the end of a romantic relationship; others are afraid to commit to a final settlement because they're afraid of what the future might hold. Still other people refuse to accept anything less than their best-case outcome and don't see the financial and emotional benefits of settlement.

If you just can't get to a settlement, arbitration and litigation are great ways of breaking the logjam. You will, without a doubt, get a resolution to your legal problem. There's a risk to each of you, of course, because you're giving up your ability to control the final resolution of your legal problem. Maybe the arbitrator or judge will make the decision you want, but you never know.

The good news, however, is that you are not doomed to a trial just because you have started a court proceeding. The vast majority of family law proceedings started in the British Columbia Supreme Court settle without a trial; many Provincial Court proceedings settle short of trial as well. Settlement is still possible even though a court proceeding has started.

You can't get the information you need

There once was a game show called Let's Make a Deal which aired for a number of years beginning in the 1960s. The idea with the show was that people would be selected from the studio audience, and then be given something of value. They were then given the choice of keeping what they'd been given or trading that initial prize for something else hidden behind a curtain or in a box. If the contestant guessed right, they might win a pile of cash, a new car or a vacation trip, but if they guessed wrong they might have to trade their initial prize for a case of beans, a Christmas sweater or a llama.

You can negotiate the settlement of a family law dispute like you're playing Let's Make a Deal, but that's a bad idea. If you can't get the information you need to know from your ex about whether you are making a good deal or a bad deal, the odds are that you're making a bad deal. In family law disputes, people usually need to know each other's incomes, the value of savings and pensions, and the value of property, as well as the amount owing on credit cards, loans and mortgages. If you cannot get this financial information from your ex, you may have no choice but to start a court proceeding.

You're concerned about family violence and threats

You may also have no choice but to start a court proceeding if:

- there's a history of family violence or other abuse in your relationship,

- you or your children need to be protected from your ex, or

- your ex is threatening to do something drastic like take the children, hide or damage property, or rack up debt that you'll be responsible for.

While many mediators and some arbitrators have special training in handling cases involving a history of family violence, there may be times when only the court can guarantee your safety and the safety of your children, and only a court order will adequately protect people or property. Even though you may have no choice but to start a court proceeding, remember that settlement is still possible.

The law

When lawyers talk about "the law", they're talking about two kinds of law: laws made by the government and the common law.

Laws made by the government are called legislation. Important legislation in family law disputes includes the Divorce Act, a law made by the federal government, and the Family Law Act, a law made by the provincial government. The government can also make regulations for a particular piece of legislation which might contain important additional rules or say how the legislation is to be interpreted. One of the most important regulations in family law is the Child Support Guidelines, a regulation to the Divorce Act.

The common law is all of the legal rules and principles that haven't been created by a government. The common law consists of the legal principles in judges' decisions, and has been developing since the modern court system was established several hundreds of years ago.

Legislation

Legislation, also known as statutes and acts, are the rules that govern our day-to-day lives. The federal and provincial governments both have the authority to make legislation, like the provincial Motor Vehicle Act, which says how fast you can go on a highway and that you need to have a licence and insurance to drive a car, or the federal Criminal Code, which says that it's an offence to stalk someone, to steal, or to shout "fire" in a crowded theatre.

Because of the Constitution of Canada, each level of government can only make legislation on certain subjects, and normally the things one level of government can make rules about can't be regulated by the other level of government. For example, only the federal government can make laws about divorce, and only the provincial governments can make laws about property.

The common law

The basic job of the courts is to hear and decide legal disputes. In making those decisions, the courts wind up doing a lot of different things. They:

- interpret, and develop rules for interpreting, the legislation that may apply to a dispute,

- interpret, and develop rules for interpreting, the words in a contract that may be the subject of a dispute,

- interpret the legal principles that may apply to a dispute, and

- interpret, and develop rules for interpreting, the past decisions of other judges.

Interpreting and applying legislation is one of the court's more important jobs. For example, section 16(6) of the Divorce Act says this about orders for parenting time:

In allocating parenting time, the court shall give effect to the principle that a child should have as much time with each spouse as is consistent with the best interests of the child.

The court has had to decide what "as is consistent with the best interests of the child" means when applying this section, and there are lots of decisions that talk about this phrase. In Young v Young, a 1993 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada, the country's top court, said this:

"By mentioning this factor, Parliament has expressed its opinion that contact with each parent is valuable, and that the judge should ensure that this contact is maximized. The modifying phrase 'as is consistent with the best interests of the child' means that the goal of maximum contact of each parent with the child is not absolute. To the extent that contact conflicts with the best interests of the child, it may be restricted. But only to that extent. Parliament’s decision to maintain maximum contact between the child and both parents is amply supported by the literature, which suggests that children benefit from continued access."

Unlike the laws made by governments, which are written down and organized, the common law is more of a series of legal concepts and principles that guide the courts in their process and in their consideration of each case. These ideas are not organized in a law, a code or a regulation. They are found in the case law: judges' written explanations of why they have decided a particular case a particular way. (A really good resource for finding case law is the website of the Canadian Legal Information Institute.)

The common law provides direction and guidance on a wide variety of issues, such as how to understand legislation, the test to be applied to determine whether someone has been negligent, and what kinds of information can be admitted as evidence at trial. However, unlike legislated laws, the common law doesn't usually apply to our day-to-day lives in the sense of imposing rules that say how fast we can drive in a school zone or whether punching someone in the nose is a criminal offence. It usually applies only when we have to go to court.

The courts

The fundamental purpose of the courts is to resolve legal disputes in a fair and impartial manner. The courts deal with all manner of legal disputes, from the government's claim that someone has committed a crime, to a property owner's claim that someone has trespassed on their property, to a shareholder's grievance against a company, to an employee's claim of wrongful dismissal.

No matter what the nature of the dispute is, the judge who hears the dispute must give each party the chance to tell their story and give a complete answer to the claims made against them. The judge must listen to each party without bias and make a fair decision resolving the dispute based on the facts and the law, including both the common law and any legislation that applies to the dispute.

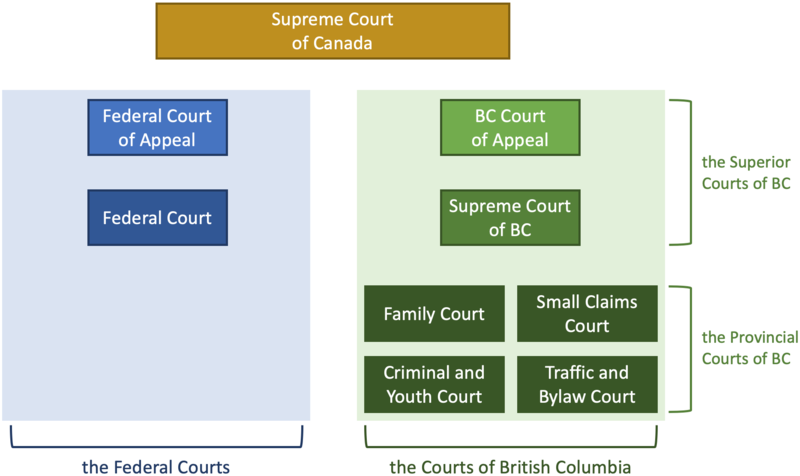

The courts of British Columbia

There are three levels of court in this province: the Provincial Court of British Columbia, the Supreme Court of British Columbia, and the Court of Appeal for British Columbia. Each level of court is superior to the one below it. A decision of the Provincial Court can be challenged before the Supreme Court, and a decision of the Supreme Court can be challenged before the Court of Appeal.

The Provincial Court

There are four divisions of the Provincial Court: Criminal and Youth Court, which mostly deals with charges under the Criminal Code and the Youth Criminal Justice Act; Small Claims Court, which deals with claims about contracts, services, property, and debt; Traffic and Bylaw Court, which deals with traffic tickets and provincial and municipal offences; and, Family Court, which deals with certain claims under the Family Law Act, the Child, Family and Community Service Act and the Family Maintenance Enforcement Act.

The jurisdiction of the Provincial Court is narrower than the Supreme Court. The Provincial Court only deals with the subjects assigned to it by the provincial government. Unless the government has expressly authorized the Provincial Court to deal with an issue, the Provincial Court cannot hear the case. For example, Small Claims Court can only handle claims with a value of between $5,001 to $35,000, and Family Court cannot deal with claims involving family property or family debt (with the exception of declaration of pet ownership between spouses), or hear claims under the Divorce Act. Each branch of the Provincial Court has its own set of procedural rules and its own court forms.

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court can deal with any legal claim and there is no limit to the court's authority, except for the limits set out in the court's procedural rules and in the Constitution. There are three kinds of judicial official in the Supreme Court: justices, masters, and registrars. Justices and masters deal with most family law problems, and only justices hear trials.

There are two sets of rules in the Supreme Court: the Supreme Court Family Rules, which apply just to family law disputes, and the Supreme Court Civil Rules, which apply to all other non-criminal disputes. Each set of rules has its own court forms.

The Supreme Court is a trial court, like the Provincial Court, and an appeal court. The Supreme Court hears appeals from Provincial Court decisions, and justices of the Supreme Court hear appeals from masters' decisions.

The Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal is the highest court in British Columbia and hears appeals from Supreme Court decisions. The Court of Appeal does not hear trials. The Court of Appeal has its own set of procedural rules and its own court forms.

The Federal Courts

The Federal Court of Canada is a second court system that is parallel to the courts of British Columbia and those of the other provinces and territories. The Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal only hear certain kinds of disputes, including immigration matters and tax problems. The Federal Court is a trial court, and the Federal Court of Appeal hears appeals from the Federal Court.

The federal courts also deal with Divorce Act claims in those rare cases when each spouse has started a separate court proceeding for divorce on the same day but in different provinces. In a situation like that, the Federal Court decides which province's court will have jurisdiction to hear the court proceeding.

The Supreme Court of Canada

The highest level of court in the country is the Supreme Court of Canada. This court has three main functions: to hear appeals from decisions of the provinces' courts of appeal; to hear appeals from decisions of the Federal Court of Appeal; and, to decide questions about the law for the federal government. Almost all of the court's time is occupied with hearing appeals.

Some criminal cases can be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada automatically. Appeals in almost all other kinds of cases, including family law cases, need the court's permission, called leave, to proceed. The Supreme Court of Canada chooses which appeals it will hear and which it won't. In general, the legal issue in a proposed appeal must have a broad public importance — the legal issue is shared by a lot of people and the case law on that issue has become confused — before the court will agree to hear the case. The Supreme Court of Canada does not hear a lot of family law cases.

Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada are final and absolute. There is no higher court or other authority to appeal to.

A handy chart

This chart shows the structure of our courts. The lowest level of court in British Columbia are the provincial courts, the highest is the Court of Appeal for British Columbia; these courts are shown on the right. The highest court in the land, common to all provinces and territories, is the Supreme Court of Canada, at the top.

Court processes

All court processes start and end more or less the same way. You must file a particular form in court and serve the filed document on the other party. After being served, the other party has a certain number of days to file a reply. If the other party replies, there is a hearing. If the other party doesn't reply and you can prove that they were served, you can ask for a judgment in default. That's about it in a nutshell. The chapter on Resolving Family Law Problems in Court, especially the sections that are continuously updated in the online version of JP Boyd on Family Law, address these processes.

In the Provincial Court, you generally start a court proceeding by filing an Application About a Family Law Matter in Form 3. The other party has 30 days after being served to file a Reply to an Application About a Family Law Matter in Form 6. Read [How Do I Start a Family Law Action in the Provincial Court?] in the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this resource for more information.

In the Supreme Court, court proceedings are usually started by filing a Notice of Family Claim, and sometimes by filing a Petition. A person served with a Notice of Family Claim has 30 days to file a Response to Family Claim and possibly a Counterclaim, a claim against the person who started the court proceeding. A person served with a Petition has 21 days to file a Response to Petition, if served in Canada, 35 days if served in the United States of America, and 49 days if served anywhere else. [How Do I Start a Family Law Action in the Supreme Court?] in the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this resource also contains more information.

Eventually, there will be a hearing, a trial, or an application for default judgment if a responding document isn't filed, in the Provincial Court or the Supreme Court. The trial will result in a final order that puts an end to the legal dispute, unless, that is, someone decides to appeal the final order.

In family law disputes, things rarely go from starting the proceeding straight to trial. Along the way you will likely have to:

- attend a judicial case conference, if you're in the Supreme Court, or a family management conference, if you're in the Provincial Court,

- make or reply to one or more interim applications,

- produce financial documents and other documents that are relevant to the claims in the dispute, and

- attend an examination for discovery, if you're in the Supreme Court.

If either party is unhappy with the result of a trial and can show that the judge made a mistake, that person can appeal the final order to another court. Orders of the Provincial Court are appealed to the Supreme Court, and orders of a Supreme Court judge are appealed to the Court of Appeal. Consult the various appeals-related guides under the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this wikibook.

You start an appeal by filing a Notice of Appeal, and serving the filed document on the other party, usually within 30 days of the date of the final order. The other party has a certain amount of time to file a Notice of Appearance in the Court of Appeal, or a Notice of Interest for appeals from the Provincial Court to the Supreme Court.

Eventually, there will be a hearing that will result in another final order that puts an end to the appeal. Appeals heard by the Supreme Court can be appealed to the Court of Appeal, and appeals heard by the Court of Appeal can be heard by the Supreme Court of Canada, but only if that court gives permission.

Trial basics

A trial is the conclusion of a court proceeding. It is the moment when each side presents their claims, the evidence they have gathered in support of those claims, and the arguments and law that support their claims to a judge. A trial ends when each side has finished presenting their evidence and arguments. In some cases the judge will give their decision right away, but it is far more common for a judge to take time to think about the evidence and the law, and decide what the right outcome is.

The usual order of a trial appears below. (Remember that in the Provincial Court, the person who starts a court proceeding is the applicant. In the Supreme Court, this person is the claimant. In both courts, the person against whom a court proceeding has started is the respondent.)

- The applicant (or claimant) presents their opening statement or opening argument to tell the judge about their case and about what their witnesses will say.

- The applicant presents their witnesses. For each witness:

- The applicant will ask the witness a series of questions, called a direct examination or an examination-in-chief.

- The respondent will ask the witness more questions, called a cross-examination.

- The applicant will ask the witness a small number of further questions, called a redirect examination.

- When the applicant has finished presenting their witnesses, the respondent will present their opening statement.

- The respondent presents their witnesses. For each witness:

- The respondent will conduct their direct examination.

- The applicant will conduct their cross-examination.

- The respondent will conduct their redirect examination.

- The applicant will present their closing argument to tell the judge why the evidence of the witnesses support the decision they want the judge to make.

- The respondent will present their closing argument.

- Sometimes, but not always, the applicant will be able to provide a short reply to the respondent's closing argument, called a surrebuttal.

- The judge makes their decision.

(Evidence at trial is almost always given by witnesses and through documents like bank records, income tax returns, and photographs that the witnesses identify. In rare cases, the evidence of a witness can be given by an affidavit or through some other statement, like a transcript of the examination for discovery of the witness, but this hardly every happens.)

In every case that goes to trial — and, to be clear, very few cases do — the judge who hears the case must first make a decision about what the facts of the case are after they have listened to the evidence, since people hardly ever agree on the facts of a case. This is called a "finding of fact." The judge then reviews the law and the rules and legal principles that might apply, and decides what law applies to the legal issues. This is called making a "finding of law." The judge makes a decision about the legal claim by applying the law to the facts.

The judge's written decision, summarizing their conclusions about the facts and the law, is called the judge's reasons for judgment. When the judge needs to think about the evidence and the law before they make a decision, the judge has reserved judgment on the case.

Appeal basics

The decision of a trial judge can be challenged to a higher court. A decision of the Provincial Court is appealed to the Supreme Court, and a decision of the Supreme Court is appealed to the Court of Appeal. Decisions of the Court of Appeal can be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, but only if the court agrees to hear the appeal.

An appeal is not a chance to have a new trial, introduce evidence that you forgot about, or call additional witnesses. You don't get to appeal a decision just because you're unhappy with how things turned out. Appeals generally only concern whether the judge used the right law and correctly applied the law to the facts. This is what the Court of Appeal said about the nature of appeals in the 2011 case of Basic v. Strata Plan LMS 0304:

"Consideration of this appeal must start, as all appeals do, recalling that the role of this court is not that of a trial court. Rather, our task is to determine whether the judge made an error of law, found facts based on a misapprehension of the evidence, or found facts that are not supported by evidence. Even where there is such an error of fact, we will only interfere with the order if the error of fact is material to the outcome."

An appeal court very rarely hears new evidence or makes decisions about the facts of a case. Most often, the appeal court will accept the trial judge's findings of fact. If the appeal court is satisfied that the trial judge made a mistake about the law, however, the appeal may succeed.

Appeals at the Supreme Court are heard by one judge; appeals at the Court of Appeal are heard by a panel of three judges. (Really important appeals are sometimes heard by a panel of five judges.) At the appeal hearing, the person who started the appeal, the appellant, will go first and try to explain why the trial judge made a mistake about the law. The other party, the respondent, will go next and explain why the trial judge appropriately considered the applicable legal principles and why the judge was right. The appellant will then be able to provide a short reply to the respondent's arguments. Sometimes the court is able to make a decision after hearing from each party but, like at trial, the court usually reserves its decision to think about the arguments that each side made.

The Helpful Guides and Common Questions part of this resource has details about the procedures for making an appeal. You may want to look at these topics:

- How Do I Appeal a Provincial Court Decision?

- How Do I Appeal an Interim Supreme Court Decision?

- How Do I Appeal a Final Supreme Court Decision?

- How Do I Appeal a Court of Appeal Decision?

Representing yourself

There is no rule that says that you must have a lawyer represent you in court. Although a court proceeding can be complicated to manage and the rules of court can be confusing, you have the right to represent yourself.

If you do decide to represent yourself in a court proceeding, you have a responsibility to the other parties and to the court to learn about the law that applies to your proceeding and the procedural rules that govern common court processes, like document disclosure, and common court processes, like making and replying to interim applications.

A good start would be to read through the other sections in this chapter on The Law for Family Matters, and You and Your Lawyer, as well as the section on The Court System for Family Matters within the Resolving Family Law Problems in Court chapter. You might also want to read a short note I've written for people who are representing themselves in a court proceeding, "The Rights and Responsibilities of the Self-Represented Litigant" (PDF).

To find out what to expect in the courtroom, read How Do I Conduct Myself in Court at an Application?. It's located in the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this resource, in the section Courtroom Protocol.

Sometimes people begin a court action with a lawyer, and then start to represent themselves. If you do this, you need to notify the other parties and the court of the change. See How Do I Tell Everyone That I'm Representing Myself?. It's located in the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this resource.

Resources and links

Legislation

- Family Law Act

- Divorce Act

- Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982

- Child Support Guidelines

- Supreme Court Civil Rules

- Supreme Court Family Rules

Resources

- The Rights and Responsibilities of the Self-Represented Litigant (PDF)

- Family Law Handbook from the Canadian Judicial Council

- Guide to Preparing for a Family Court Trial in Provincial Court from the Provincial Court of BC

- The National Self-Represented Litigants Project resources

- Legal Aid BC's Family Law in BC website

Links

| This information applies to British Columbia, Canada. Last reviewed for legal accuracy by JP Boyd, 18 November 2023. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||