Resolving Family Law Problems in Court Overview

|

Given that BC's courts are in an especially active state of transformation, and to offer you in-depth and up-to-date information about trial and application procedures as these evolve, we direct readers of the 4th edition of JP Boyd on Family Law to the online version of this chapter.

For more information about this decision and the ongoing court reforms, read on and see the Introduction on page 1. |

Note for readers of the fourth edition[edit]

The process of starting a court proceeding and wrapping it up at trial can be complicated. The details matter. You need to know the procedures, and there are many places you need to look to learn them:

- There are formal statutes that contain important laws affecting litigation (such as laws dealing with evidence, causes of action, judge's power to make an order, limitation periods, court jurisdiction, divorce, and so on), which are debated and passed by legislature or parliament.

- There are court rules and forms issued by government as regulations, which are legally binding and dictate the majority of what happens once a case is filed.

- Then there are practice directions issued by the chief justices and judges for their respective courts, which tend to instruct how rules are carried out in practice and when dealing with registry or scheduling desks, as well as with court technology.

- And then there are common law rules (yes, more rules!) which evolved over centuries and change incrementally as judges refine them. These influence what someone can give as evidence, how a judge assesses credibility, and when a judge will exercise inherent jurisdiction and wield their power.

Most of the time, major procedural changes are planned ahead of time. Maybe one major piece changes, but not many things at once. In 2010, the British Columbia Supreme Court overhauled its family rules and changed all the form names. That was a major change, but it happened years before big changes followed with the coming into force of the Family Law Act. And procedure remained fairly stable after that. A new form or two, some tweaks to the language in the rules for clarity were made, but not too much.

We released the 3rd edition of JP Boyd on Family Law in 2019, and we then learned about the next major change on the horizon: amendments to the Divorce Act. This would mean significant changes to court forms and rules, and meant 2020 would be a good time to follow up with a fourth edition. As we planned to do just that, in February 2020 the BC Government revealed an amendment to the Family Law Act that would change the law around arbitration of family law disputes. This was another update we could manage in the fourth edition.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic struck.

From March 2020 forward, any notion that BC's court procedure was supposed to change gradually and deliberately went out the window. Practice directions from the Chief Justice of the BC Supreme Court and Chief Judge of the Provincial Court were re-writing the rules of court on an emergency basis — literally pursuant to Ministerial Order M121/2020 issued under the Emergency Program Act by the Minister of Public Safety — and on the fly. Courtrooms that had only ever run in person, were now being run in Zoom from people's living rooms. The courts' joint policy restricting electronic devices in the courtroom was swiftly revised. Electronic devices suddenly were the courtroom.

It was a time of frantic, unprecedented disruption. Between March 2020 and June 2022 the BC Supreme Court issued 57 different Covid-19 Notices that affected everything imaginable related to procedure.

It was, to put it mildly, no time to try and describe what going to court looked like in the province, and commit that description to the printed page.

In May 2021, the Provincial Court revised the Provincial Court Family Rules while also expanding its use of Early Resolution Registries. These were big changes which resulted in almost all of the discussion and references to rules, forms, and procedures in the 3rd edition of JP Boyd on Family Law to be out-of-date. Not only did the names of the Provincial Court Family Rules and accompanying forms change, not only did their numbering change, but their purpose changed. The new rules aimed to help self-represented litigants with easier to understand forms and ensure attendance at court by telephone, video, or in-person, only when something substantial would happen.

If our purpose is to print a book that educates on how to bring or defend a case before British Columbia's family courts, then we want to be reasonably sure that the information we tell you is accurate — and not only at the moment we print it, but for a reasonable window of time afterwards too.

As we prepared to print this edition, it became more clear that the transformative work and experimentation by the courts will likely mean further changes to court rules and procedures heading into 2024. The Provincial Court continues to solicit feedback about how the new forms, rules, and types of registries are working for court participants. There is no reason to expect that this is the end of the reform work.

We have had to make a choice. We could have tried to generalize our discussion of the litigation process by minimizing specific references to rules, forms, and steps in a proceeding so that we only talked about general principles and perhaps strategies for thinking about litigation. This could mean it would not matter if the Provincial Court Family Rules changed again three months after we printed.

On the other hand, if the greater benefit to readers is that we go into detail about court procedures, then this chapter is better off being placed online where it can be updated. The print version you are holding will therefore tell the story of why it does not contain a detailed chapter on Resolving Family Law Problems in Court. It offers a link to the full version. And below is an overview on going to court instead.

Overview on going to court[edit]

The online version of this chapter is actually three chapters. One is an overview much like this print version you're reading. And the other two discuss — for each trial court separately — the process for starting and replying to court proceedings, making applications before trial, completing a trial, and enforcing or changing orders.

This overview provides a thumbnail sketch of the basic court process common to all family law court proceedings.

Hold on for a minute, do you really have to go to court?[edit]

Sometimes, you really have no choice except to start a court proceeding. But you should think twice before you do, and make sure that litigation is your best choice.

The end of a relationship, especially a long relationship, is an emotionally charged, stressful time. Court is not the only way there is to solve a problem, even though it might be really tempting to drop the bomb and hire the most aggressive lawyer you can find. Before you decide to go to start a court proceeding, think about these things first:

Your future relationship with your ex. Right now you might hate your ex and want to make their life miserable. You might not feel that way in a year or two. If you don't have children, it might be entirely possible for you to simply walk out of each other's lives and into the sunset. If you do have children, however, you don't have that option. Your relationship as lovers and partners might be over, but your relationship as parents will continue forever.

Your children, and your relationship with your children. Your children will be aware that there is a certain degree of conflict between you and your ex, an understanding that will differ depending on the children's ages. When parents are engaged in a court proceeding, it can be tremendously difficult to shield the children from the litigation, from your emotional reactions to the litigation, and from your conflict with their other parents. It can also be difficult to refrain from using the children as weapons in the litigation. This will always affect the children adversely, and often in ways you don't expect.

Your own worries and anxieties. Litigation is always an uncertain process. No one, not even your lawyer, can guarantee that you will be completely successful about any particular issue. At the end of the day, fundamental decisions will be made by a complete stranger — a judge — about the things that matter the most to you, and the judge's decision is not something you can predict with any certainty. On top of that, litigation, especially when you're doing it yourself, is very stressful. The forms and processes will be new to you, and each court appearance will likely be a fresh cause of anxiety and uncertainty.

Your wallet. If you opt to hire a lawyer, be prepared to pay and to pay a lot. Sometimes a lawyer can help you get things done quickly and with a minimum of fuss and bother, but if emotions are running high, you stand to pay a whopping legal bill, especially if you go all the way through to trial. Even if you don't hire a lawyer, litigation can be expensive, and if you are unsuccessful you can also be ordered to pay the other side's court costs.

There are other ways of solving your problem than litigation. Going to court is only one of the ways to bring your dispute to an end. Other, less confrontational and less adversarial approaches include negotiation, mediation, collaborative negotiation and arbitration. All of these other approaches generally cost a lot less, and, because they are cooperative in nature, they'll give you the best chance of maintaining a working relationship with your ex after the dust has settled. These options are discussed in more detail in the chapter Resolving Family Law Problems out of Court.

Now, in fairness, there are times when going to court may be your only choice. It may be critical to start a court proceeding when:

- there has been family violence in your relationship, whether involving you or your children,

- there have been threats to your physical safety, or to the safety of your children,

- your ex has threatened to take the children out of town, out of the province, or out of the country against your wishes,

- there is a threat or a risk that your ex will damage, hide, or dispose of property,

- you urgently need to get some financial help,

- negotiations have failed and, despite your very best efforts, you and your ex can't agree on how to solve your differences, or

- your ex refuses to communicate with you about the legal issues that need to be resolved.

While you should think twice before deciding that court is your only option, starting a lawsuit doesn't mean that you can't continue to try to negotiate a resolution outside of the court process.

For more information about the emotions that surround the end of a long-term relationship, and how these emotions can affect the course of litigation, read the section Separating Emotionally in the chapter Separating and Getting Divorced. You should also track down and read a copy of Tug of War by Mr. Justice Brownstone from the Ontario Court of Justice. He gives a lot of practical advice about the family law court system, when it works best and when it doesn't work at all.

You might also want to read a paper I wrote for people who are representing themselves in court proceedings, "The Rights and Responsibilities of the Self-Represented Litigant".

Okay, I'm going to court. Which court do I go to?[edit]

Before getting any deeper into this chapter, go review the chapter Understanding the Legal System for Family Law Matters, in particular, the section on The Court System. What you'll learn there is that there are two courts that hear trials in British Columbia, the Provincial Court and the Supreme Court, and that these courts are very different from one another.

The Provincial Court deals with issues relating to parenting children, child support, spousal support, and orders protecting people under the Family Law Act. The Supreme Court has the authority to deal with all of those issues, but can also deal with issues about parentage, dividing property and debt, and orders protecting property under the act. Only the Supreme Court has the authority to make orders under the Divorce Act, including orders for divorce. This chart shows which trial court can deal with which family law problem:

Supreme Court Provincial Court Claims under the Divorce Act All claims Claims under the Family Law Act All claims Some but not all claims Divorce Yes Guardianship and

parenting childrenYes Yes Time with children Yes Yes Child support Yes Yes Children's property Yes Spousal support Yes Yes Family property and

family debtYes Pets only Orders protecting people Yes Yes Orders protecting property Yes

The rules of the Supreme Court can be very complicated and fees are charged for many steps in the court process, including filing the paperwork that starts a court proceeding, making an application, or going to trial. The Provincial Court process is intended to be more affordable and easier to navigate without a lawyer's help. Visit the link to the more in-depth version of this chapter at the beginning of this section, or go to Legal Aid BC's Family Law website for more information, including If you have to go to court and Trials in Provincial Court.

It is possible to start a proceeding in the Provincial Court to deal with things like child support, and then start a proceeding in the Supreme Court to get a divorce and deal with things like property. It can be complicated to split your family law issues between two courts. A lot of people find it easier just to deal with everything in one court, but because of the limits of the authority of the Provincial Court, the Supreme Court is the only choice available.

What's the court process going to be like?[edit]

If you need the court to make an order about something, even about something you might agree to, like a divorce, you must start a court proceeding. Court proceedings are also called cases, lawsuits, and actions. There are two types of court proceedings, criminal matters and civil matters. Criminal matters concern the government's claim that someone has broken a criminal law, like the Criminal Code or the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Civil matters concern claims between people, companies and governments. Family law cases are civil matters.

A few definitions[edit]

Before going further, it'll help to learn some of the terminology used in litigation. (You can call find more definitions in the Terminology pages of this resource.)

- Family law proceeding: A court proceeding that is started to resolve a family law dispute, and other civil claims related to that dispute.

- Claimant or Applicant: The person who starts a court proceeding in the Supreme Court is the claimant. In the Provincial Court, this person is the applicant. (In this section, claimant refers to both claimants and applicants.)

- Respondent: The person or people against whom a court proceeding is brought are the respondents.

- Parties: The claimant and the respondent are, together, called the parties to the court proceeding.

- Claim or Application: The document that is filed to start a court proceeding in the Supreme Court is a Notice of Family Claim or, less often, a Petition. In the Provincial Court, court proceedings are started with an Application About a Family Law Matter. (In this section, claim refers to all of these documents.)

- Reply and Counterclaim: A respondent who objects to all or some of the orders sought by a claimant in the Supreme Court will file a Response to Family Claim and sometimes a Counterclaim: A Counterclaim lets a respondent make claims of their own against a claimant. In the Provincial Court, a respondent will file a Reply to an Application about a Family Law Matter, which includes a section to make a counterclaim against an applicant. (In this section, reply refers to all of these documents.)

- Pleadings: The basic documents that are used to start and reply to a court proceeding are called the pleadings. In most Supreme Court family law proceedings, the pleadings are the Notice of Family Claim, the Response to Family Claim, and, usually, a Counterclaim. In most Provincial Court proceedings, the pleadings are the Application About a Family Law Matter and the Reply to an Application about a Family Law Matter.

- Trial: The formal hearing of a claim, a response to a claim and a counterclaim by a judge, following which the judge makes an order resolving all of the claims and counterclaims made in the court proceeding.

The court process in a nutshell[edit]

Visit Legal Aid BC's Family Law website or visit the link to the in-depth online chapter of this resource at the beginning of this section to learn about the current Provincial Court process. Proceedings in the Supreme Court, other than proceedings in criminal matters, work more or less as follows.

The claimant starts the proceeding. The person who wants a court order, the claimant, starts a court proceeding by filing a claim in court and serving the filed claim on the respondent. The claims says what orders the claimant wants the court to make. Serving the filed claim involves having the claim hand-delivered to the respondent by someone other than the claimant.

The respondent files a response. The respondent has a certain amount of time after being served to reply to the court proceeding by filing a response in court. (The number of days is set out in the document filed by the claimant to start the court proceeding.) The response says which of the orders sought by the claimant are agreed to by the respondent and which are opposed. The respondent can also ask the court for orders they want. If the respondent wants a court order, the respondent will file a claim of their own, called a counterclaim. The response and any counterclaim must be delivered to the claimant.

The claimant files a reply. The claimant has a certain amount of time after receiving the counterclaim to reply to any claim made by the respondent by filing a reply in court. The reply says which of the orders sought by the respondent are agreed to by the claimant and which are opposed. The claimant's reply must be delivered to the respondent.

The parties exchange information. Next, the parties gather the information and documents they need to explain why they should have the orders they are asking for. Because trials are not run like an ambush, the parties must exchange their information and documents well ahead of trial. This way everyone knows exactly what is going on and how strong each person’s case is. There are different processes in Supreme Court and Provincial Court for exchanging information. For more details, see the section Starting a Court Proceeding in a Family Matter in this chapter.

The parties attend case conferences. Case conferences are meetings with judge to talk about the court proceeding. They often provide an opportunity to talk about settlement option and to ask for orders about steps in the court proceeding as the proceeding heads to trial. For more about case conferences, see the section about Case Conferences in this chapter.

Each party answers questions out of court. In court proceedings before the Supreme Court, each party is usually required to attend an examination for discovery. This is an opportunity for each party to ask the other parties questions about things that are relevant to the legal issues so that everyone knows the evidence that will be given at the trial. This is also an opportunity to ask each party to provide more documents.

Go to trial. Assuming that settlement isn't possible, court proceedings are resolved by trials. At trial, each of the parties presents their evidence and explains to the judge why the judge should make the orders they're asking for. The judge may make a decision resolving the decision on the spot; most often, however, the judge will want to think about the evidence and the parties' arguments and will give a written decision later, often weeks or even months later.

Remember that you can continue to try to negotiate a settlement with the other party at every stage of this process. You can even decide to try mediation in the middle of a court proceeding, and, if you are getting tired of the court process or are worried about how long it will take to have a trial, you can abandon the court process altogether and go to arbitration.

While working your way through the court process, you may find that it's sometimes necessary to ask for interim orders. These are temporary orders that address a short-term problem or need, or that help the court proceeding get to trial. In family law cases, people often ask for interim orders to protect someone when family violence is an issue, to deal with the payment of child support or spousal support, to get a parenting schedule in place, to determine how the children will be cared for, or to protect property while waiting for the trial.

The process for interim orders is a miniature version of the larger process for getting a claim to trial.

The applicant starts the application. The person who wants the interim order, the applicant, starts the application process by filing an application and an affidavit in court, and delivering the filed application and affidavit on the other party, called the application respondent. The application describes the orders the applicant wants the court to make. The affidavit describes the facts that are relevant to the application and the orders the applicant is looking for. For more information about affidavits, see the page, How Do I Prepare an Affidavit?, in the Helpful Guides & Common Questions part of this resource.

The application respondent files a response. The application respondent, the person who is responding to the application, has a certain amount of time after receiving the application and affidavit to file a response and an affidavit in court. The response says which orders the person agrees to and which they object to. The affidavit describes any additional facts that are important to the application. The response and affidavit must be delivered to the applicant.

The applicant may file another affidavit. The applicant has a certain amount of time after receiving the application respondent's materials to file another affidavit in court. This affidavit is a response to the application respondent's affidavit and describes any additional facts that are important to the application. This affidavit must be delivered to the application respondent.

Go to the hearing. Assuming that settlement isn't possible, the only way to resolve the application is to have a hearing. At the hearing, each of the parties will present the evidence set out in their affidavits and explain to the judge why the judge should, or shouldn't, make the orders asked for. Most of the time the judge will make a decision resolving the decision on the spot; sometimes, however, the judge will want to think about the evidence and the parties' arguments, and will give a written decision later.

For more details follow the link to the online chapter section on interim applications at the beginning of this section.

There are lots of details we've skipped over in this brief overview, including details about important things like experts, case conferences, and the rules of evidence, but this is the basic process in a nutshell. These other details are governed by each court's set of rules. The rules of court are very important, and the rules of the Provincial Court are very different than the rules of the Supreme Court.

You can probably guess that getting a court proceeding to trial can be a long and involved process, and that if you have a lawyer representing you, it'll cost a lot of money to wrap everything up. Making these procedural delays worse, trial dates are often in short supply. In Vancouver, for example, you may not be able to get dates for a one-week trial any sooner than 18 months.

It's important to remember that you and the other party can agree to resolve your dispute out of court at any time in this process. If you haven't done so already, please read the chapter Resolving Family Law Problems out of Court.

Rules promoting settlement[edit]

Just because a court proceeding has started, it doesn’t mean you will be going to court. The majority of cases settle prior to trial; in fact, the number of civil court proceedings in the Supreme Court of British Columbia that are resolved by trial is less than 5%! There are a few reasons why this is the case. First, trials are time-consuming and expensive. Second, you can never be absolutely sure what the result is going to be. You're always rolling the dice when you go to trial. Third, you can usually find a way to settle a dispute sooner than the first available trial date.

It also helps that the rules of court — both the Provincial Court Family Rules and the Supreme Court Family Rules — are written to promote settlement and find ways of pushing litigants toward the offramps that lead away from trial. (It says something, I think, that the rules of the province's two trial courts are designed to discourage trials.) This section talks about these offramps, the rules that are intended to encourage people to propose settlement options, the rules that provide judges to help people negotiate settlements, and the rules that penalize people for going to trial without fully thinking things through.

Introduction to rules promoting settlement[edit]

There are many reasons why it's important to resolve family law disputes other than by trial. From the court's point of view, when separated spouses or parents are able to reach a settlement of their legal problems, their agreement:

- helps to protect the children from their ongoing conflict

- frees up valuable judicial and administrative resources for other cases, and,

- decreases the likelihood that the dispute will require ongoing court hearings in the future.

From the point of view of the spouses or parents involved in the dispute, making an agreement:

- is cheaper and faster than going to trial,

- is more likely to give you more of what you want than a judicial decision,

- shows you and your ex that you can resolve even difficult disputes on your own, and

- resolves disputes and lets you move on with your life more quickly.

Settling a family law dispute gives spouses or parents a lot more personal control and creativity about the resolution of their dispute than is possible in court. It also gives everyone the best chance of being able to work together in the future.

(Lawyers also have an interest in settling matters, believe it or not, for all of the same reasons as the courts and the parties. As well, lawyers have a professional and an ethical duty to pursue settlement wherever possible, provided that a proposed settlement is not an unreasonable compromise of their clients' interests. This duty is so important that it has been written into lawyers' Code of Professional Conduct.)

The legislation on family law and the rules of court for family law proceedings have evolved over the last two or three decades to provide additional opportunities and incentives for settlement, and steer people out of court and away from trial whenever possible. In fact, the first division of Part 2 of the provincial Family Law Act is titled "Resolution Out of Court Preferred," and begins with a statement in section 4 which says that the purposes of the Part are to:

(b) to encourage parties to a family law dispute to resolve the dispute through agreements and appropriate family dispute resolution before making an application to a court;

(c) to encourage parents and guardians to

(i) resolve conflict other than through court intervention, and

(ii) create parenting arrangements and arrangements respecting contact with a child that is in the best interests of the child.

Under section 8(2), lawyers are required to "discuss with the party the advisability of using various types of family dispute resolution to resolve the matter." (That awful, clumsy term family dispute resolution is defined in section 1(1) as including mediation, arbitration, and collaborative negotiation.) Lawyers have the same sort of obligation under section 7.7 of the federal Divorce Act:

(2) It is also the duty of every legal adviser who undertakes to act on a person’s behalf in any proceeding under this Act

(a) to encourage the person to attempt to resolve the matters that may be the subject of an order under this Act through a family dispute resolution process, unless the circumstances of the case are of such a nature that it would clearly not be appropriate to do so;

(b) to inform the person of the family justice services known to the legal adviser that might assist the person

(i) in resolving the matters that may be the subject of an order under this Act, and

(ii) in complying with any order or decision made under this Act; and

(c) to inform the person of the parties’ duties under this Act.

Whether or not your lawyer gives you this encouragement or information, section 7.3 of the Divorce Act requires you, and the other parties to your court proceeding, to at least try to resolve your disagreements out of court:

To the extent that it is appropriate to do so, the parties to a proceeding shall try to resolve the matters that may be the subject of an order under this Act through a family dispute resolution process.

In general, you should try to resolve a court proceeding without going to trial if you can. However, your settlement, whether it's reached with the help of a judge or not, must be fair and reasonable and roughly within the range of what would have happened if the issues in your proceeding had been resolved at trial. While it's always a relief to wrap up a court proceeding, if the settlement is really unfair to either party a return to court may be inevitable!

The Provincial Court[edit]

In 2021, BC received a complete overhaul of its Provincial Court Family Rules, and into 2024 there are still signs that the courts are not quote done tinkering with them. Visit the link at the beginning of this section to see our more in-depth online chapter, or visit Legal Aid BC's Family Law website for more guidance on what the new rules require you to do, and how this can change depending on where you are located. The purpose of the revamped Provincial Court Family Rules is aimed at promoting settlement, helping parties resolve their case by agreement, or to help them obtain a fair outcome in way that minimizes conflict and promotes cooperation between parties.

Section 8 of the Rules clearly states that “parties may come to an agreement or otherwise reach resolution about family issues at any time”. That means that even if it’s the morning of your trial and you’re all ready to go, you and your ex can decide to settle without going to trial.

The new Rules have also divided various courthouse registries into different categories. For example, Victoria is an Early Resolution Registry, Vancouver (Robson Square) is a Family Justice Registry, and Abbotsford is a Parenting Education Program Registry. Legal Aid BC's Family Law website has more information on each of these types of registry.

No matter the registry in which you find yourself, there are certain steps you have to take before you’ll be able to argue before a judge. In most cases, the first time that parties will be before a judge will be at what’s called a Family Management Conference (FMC), which is a settlement-focused appearance. If settlement isn’t possible at the FMC, the judge can make orders (by consent or not), make interim orders to address needs until resolution is reached, and determine next appropriate steps.

A notable difference between Supreme Court and Provincial Court is that costs are not payable in Provincial Court. That said, a word of caution: if a judge decides that cross examining an expert witness was unnecessary, then the party who decides to cross examine that expert can be responsible for the costs associated with that, which can be in the thousands of dollars.

The Supreme Court[edit]

The rules of the Supreme Court allow the court to refer people to other dispute resolution services, much like the rules of the Provincial Court. In addition to offering carrots like this, the Supreme Court Family Rules also include a stick or two. The biggest stick is the court's jurisdiction to make an order about costs. An order for costs is an order that one party pay for some or all of the expenses another party incurred dealing with the court proceeding. Costs are usually, but not always, awarded to the party who is most successful at trial. They can also be awarded to punish bad behaviour in the course of a court proceeding, or to penalize a party who failed to accept a reasonable settlement proposal.

Judicial case conferences[edit]

Rule 7-1 requires that the parties to a court proceeding attend a judicial case conference before they can send a Notice of Application or an affidavit to another party. This usually has the effect of making judicial case conferences a mandatory part of all family law cases in the Supreme Court. A judicial case conference, usually referred to as a JCC, is a relatively informal, off-the-record, private meetings between the parties, their lawyers, and a master or judge in a courtroom.

Rule 7-1(15) gives the court a broad authority to take steps and make orders to promote the settlement of the court proceeding. Among other things, the master or judge may:

- identify the issues that are in dispute and those that are not in dispute and explore ways in which the issues in dispute may be resolved without recourse to trial;

- mediate any of the issues in dispute; and,

- without hearing witnesses, give a non-binding opinion on the probable outcome of a hearing or trial.

What's really cool about JCCs is that, under Rule 7-1(1), "a party may request a judicial case conference at any time, whether or not one or more judicial case conferences have already been held in the family law case." If there's a chance of settlement as you head toward trial, take advantage of this rule and book another JCC!

JCCs are discussed in more detail in the section on Conferences and Supreme Court Family Law Proceedings in the online chapter about Supreme Court litigation.

Settlement conferences[edit]

Settlement conferences are available under Rule 7-2 at the request of both parties. Settlement conferences are are relatively informal meetings between the parties, their lawyers, and a master or judge that are solely concerned with finding a way to settle the court proceeding.

Settlement conferences are private and are held in courtrooms that are closed to the public. Only the parties and their lawyers are allowed to attend the conference, unless the parties and the judge all agree that someone else can be present. They are held on a confidential, off-the-record basis, so that nothing said in the conference can be used against anyone later on.

Offers to settle[edit]

You can make a formal offer to settle at any time during a court proceeding. An "offer to settle" is a proposal about how all of the claims made in the claimant's Notice of Family Claim and in the respondent's Counterclaim will be wrapped up. A party receiving an offer to settle can decide to accept the offer or to refuse it. There are, however, important consequences for refusing a reasonable offer under Rule 11-1 that we'll talk about in a second.

It's important to know, first, that offers to settle are private and confidential. The point of this is to let someone make an offer to resolve a court proceeding without being held to that position if the offer is rejected and the case goes to trial. You want to be able to make a serious proposal that offers to compromise your position without being stuck with that compromise at trial. In fact, Rule 11-1 expressly states that no one can tell a judge that offer has been made until the case is wrapped up:

(2) The fact that an offer to settle has been made must not be disclosed to the court or jury, or set out in any document used in the family law case, until all issues in the family law case, other than costs, have been determined.

The stick shows up in subrules (5) and (6) when comparing the results of the trial against the terms of an offer to settle that was refused. These parts of Rule 11-1 say that:

(5) In a family law case in which an offer to settle has been made, the court may do one or more of the following:

(a) deprive a party of any or all of the costs, including any or all of the disbursements, to which the party would otherwise be entitled in respect of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle;

(b) award double costs of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle;

(c) award to a party, in respect of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle, costs to which the party would have been entitled had the offer not been made;

(d) if the party who made the offer obtained a judgment as favourable as, or more favourable than, the terms of the offer, award to the party the party's costs in respect of all or some of the steps taken in the family law case after the date of delivery or service of the offer to settle.

(6) In making an order under subrule (5), the court may consider the following:

(a) whether the offer to settle was one that ought reasonably to have been accepted, either on the date that the offer to settle was delivered or served or on any later date;

(b) the relationship between the terms of settlement offered and the final judgment of the court;

(c) the relative financial circumstances of the parties;

(d) any other factor the court considers appropriate.

Let's break this down a bit. What these subrules essentially say is that even if you were successful at trial, you may have to pay costs to the other side if their offer to settle was better than, or as good as, the result of the trial! The court may decide to:

- withhold an award of costs that you would normally be entitled to;

- make you pay some or all of the costs of the other side; and,

- make you pay double the normal costs of the other side after the date the offer was delivered to you.

Ouch. It pays to pay attention to an offer to settle.

To qualify as an offer to settle under Rule 11-1 an offer must:

- be in writing;

- be served on all parties to the court proceeding; and,

- include this sentence

"The [Claimant or Respondent], [name of party], reserves the right to bring this offer to the attention of the court for consideration in relation to costs after the court has pronounced judgment on all other issues in this proceeding."

An offer to settle must meet these requirements if the party making the offer is going to ask the court for a costs order under Rule 11-1(5).

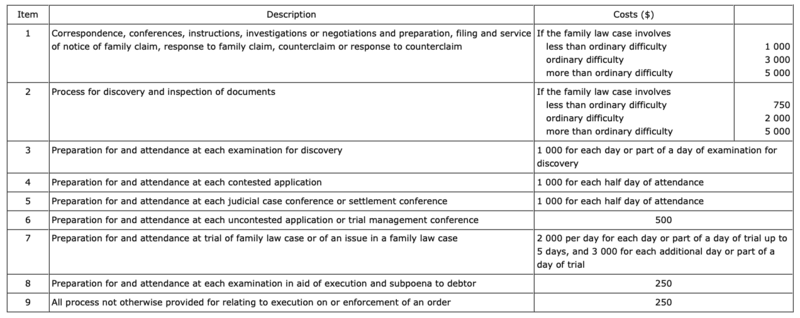

Costs[edit]

In the Supreme Court, a party may ask for their costs of an application, of a trial or of the whole of a court proceeding under Rule 16-1. "Costs" are a partial payment of the expenses and legal fees incurred by a party to a court proceeding, and are calculated under a schedule included in the Supreme Court Family Rules. Costs normally don't amount to more than approximately 30% of a party’s actual legal fees.

Normally, the party who gets most of what they asked gets an order that the other side pay their "costs," but there are exceptions. In general, costs are a sort of idiot tax designed to punish a litigant who has unreasonably started or defended a court proceeding. Say, for example, you were hit by a car and you sue the driver for $10,000. Here are some possible outcomes and how costs might work if the driver refuses to pay and defends your claim.

- You are successful at trial and get an award of $10,000. You would get your costs because the driver was an idiot for refusing to pay the money you asked for and making both of you go through a trial.

- You are successful at trial and get an award of $1,000. Even though you were successful, the driver would probably get their costs because you had demanded an unreasonable amount and the driver was right to defend your claim. You were an idiot for asking for too high an amount of money, which forced the driver to go through a trial.

- You are unsuccessful at trial. The driver would get their costs because you were an idiot for suing the driver in the first place. Your unreasonable behaviour forced the driver to go through a trial.

The schedule that is used to calculate the amount of costs payable is in Appendix B of the Supreme Court Family Rules. Under that schedule, you get a specific amount of money for specific steps taken in a court proceeding. The amount you get varies depending on whether the court proceeding was of less than ordinary difficulty, of ordinary difficulty, or of more than ordinary difficulty. "Ordinary difficulty" is the default if the court that makes a costs order makes no order about the difficulty of the court proceeding. Here's the list of those steps and the amounts payable depending on difficulty:

In addition to costs calculated under the schedule, a party who gets their costs also usually gets reimbursed for the money they spent on reasonable and necessary disbursements as well. Disbursements are out-of-pocket expenses for things like court filing fees, witness fees, transcripts, experts’ fees, photocopies, couriers, postage, and the like.

The likelihood of a cost award being made after a hearing or trial can provide a strong incentive for people to try and settle their court proceeding. It can encourage parties to be more reasonable in their positions and try to reduce the number of issues that need court intervention.

For more information about costs, see the Legal Services Society's Family Law website's information page If you have to go to court under the section "Costs and expenses."

The Notice to Mediate Regulation[edit]

Under the Notice to Mediate (Family) Regulation, someone who is a party to a court proceeding in the Supreme Court can make the other parties go to mediation by serving a Notice to Mediate on them.

A Notice to Mediate must be served at least 90 days after the Response to Family Claim is filed but at least 90 days before the scheduled trial date. Once the Notice is served, the parties must attend mediation unless:

- a party has triggered a mediation meeting using a Notice to Mediate;

- there is a protection order against a party;

- the mediator decides that the mediation is not appropriate or will not be productive; or,

- the court orders that a party is exempt because, in the court’s opinion, it is "impracticable or materially unfair" to require the party to attend.

The Notice to Mediate (Family) Regulation provides the guidelines for proceeding with the mediation. In a nutshell:

- the parties must jointly appoint a mediator within 14 days after service of the Notice to Mediate, and if they can't agree on a mediator, any of them may apply to a roster organization for the appointment of a mediator;

- the mediator must have a pre-mediation meeting with each party to screen for power imbalances and family violence, and talk about preparing for the mediation;

- the parties sign the mediator's participation agreement; and,

- the parties attend a mediation meeting, which concludes when the legal issues are resolved or when "the mediation session is completed and there is no agreement to continue."

It seems unlikely that a mediation that people are forced to attend could produce a settlement. However, even compulsory mediation sometimes works. While no one is going to be happy being compelled to do something they'd rather avoid, if the process results in a settlement, it's probably worth it. The time and money spent on the mediation process will be a fraction of the time and money you'll spend on trial.

Resources and links[edit]

Again, we encourage readers to visit the online version of this chapter for more in-depth and up-to-date information about Supreme Court and Provincial Court litigation and procedure topics: https://bit.ly/JPBOFL

Legislation[edit]

- Provincial Court Family Rules

- Provincial Court Act

- Supreme Court Family Rules

- Supreme Court Act

- Court of Appeal Rules

- Court of Appeal Act

- Court Rules Act

Resources[edit]

- Provincial Court Practice Directions

- Supreme Court Family Practice Directions

- Supreme Court Administrative Notices

- Court of Appeal Practice Directives

- Tug of War by Mr. Justice Brownstone

- "The Rights and Responsibilities of the Self-Represented Litigant" (PDF) by John-Paul Boyd

Links[edit]

- Legal Aid BC's Family Law website information on Provincial Court process:

- Courts of British Columbia website

- Provincial Court website

- Supreme Court website

- Supreme Court Trial Scheduling

- Court of Appeal website

- Guidebooks from the BC Supreme Court website

- Justice Education Society's Court Tips for Parents (videos)

| This information applies to British Columbia, Canada. Last reviewed for legal accuracy by JP Boyd, 23 November 2023. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||